A Developer's Guide to Processes

24 Aug 2020Process

In computing, a process is the instance of a computer program executed by one or many threads. It contains the program code and its activity.

Ignoring the thread portion in this definition, we can define a process as an instance of an executing computer program.

The computer program doesn’t have to be large or complex. Any program that can execute validly is considered a process.

Short-lived process

A program that runs briefly and exits is considered a process.

x = 1

print("I'm a short-lived process")

Long-running process

Running an infinite loop is considered a process.

while True:

print("I'm a long-running process")

time.sleep(1)

While these are simple programs, more complex programs such as a web server or a calendar application would also be considered processes.

Process per instance

A single instance of a program is one process. Multiple instances of a program would be multiple processes.

For example, if you open two terminals and run a program in each terminal, you would have two separate processes. For a web server, scaling it to three servers would mean you have three different processes.

We are referring to parent processes here. When programs are executed, they create a parent process. They may or may not fork or spawn child processes. We will cover this in the “Process Creation” section.

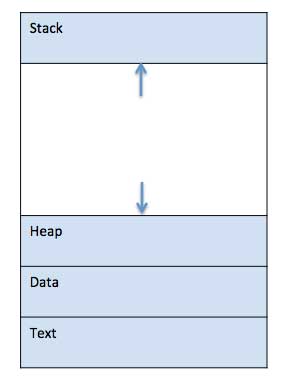

Process Memory

When a program is loaded and executed, it’s resulting process is divided into four sections in memory: stack, heap, text, and data.

Text

The text section contains the compiled program code.

Data

The data section stores global and static variables.

Heap

The heap is used for dynamic memory allocation for a process during run time.

Stack

The stack is used for local variables. Space on the stack is reserved for local variables when declared, and space is freed up when the variables go out of scope.

Note that the stack and the heap start at opposite ends of a process’s free space and grow towards each other. If they ever meet, then either a stack overflow error will occur, or else a call to

newormallocwill fail due to insufficient memory available.

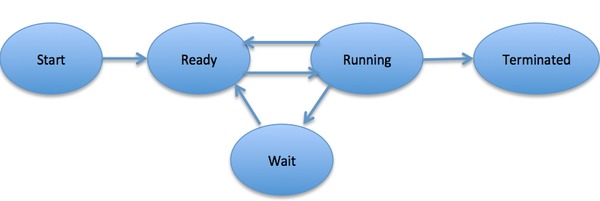

Process State

During the lifecycle of a process, it may be in one of five states.

- Start - Initial state when a process is first started or created.

- Ready - Ready processes are waiting to have the processor allocated to them by the operating system to run.

- Running - Once the process has been assigned to a processor by the OS scheduler, the process state is set to running and the processor executes its instructions.

- Waiting - Process moves into the waiting state if it needs to wait for a resource, such as waiting for user input, or waiting for a file to become available.

- Terminated - Once the process finishes its execution or is terminated by the operating system, it is moved to the terminated state.

Some processes might cycle between the states of ready, running, and repeatedly waiting due to their program instruction (long-running process example). Other processes might not need to wait and will go from the start, ready, running, and then to terminated (short-lived process example). The lifecycle of a program will depend on the underlying program.

Process Control Block (PCB)

Process control block is the information the operating system stores about processes. The PCB stores the following information.

- Process State - Current state of the process i.e. ready, running, waiting, etc.

- Process ID - Unique identification of each process in the operating system.

- Pointer - A pointer to parent process

- Program Counter - A pointed to the address of the next instruction to be executed for the process.

- CPU registers - Various CPU registers where processes need to be stored for execution when in running state.

- CPU-Scheduling information - Process priority and scheduling information.

- Memory-Management information - Information about page tables or segment tables and memory limit.

- Accounting information - Amount of CPU used for process execution, time limits, execution id, etc.

- I/O Status information - List of I/O devices allocated to the process.

While it’s important to be aware of each piece of information that a operating system stores about a process, the ones I often pay attention to are: process state, process id, pointer, and accounting information.

Types of processes

Foreground Process

Foreground processes require a user to start them or interact with them. They are initialized by running a command in a shell or starting applications through a graphical user interface (GUI).

# Running ls is considered a foreground process

> ls

Applications Desktop Documents Downloads Dropbox Library Misc Movies Music Pictures

When running a foreground process through a shell, you have to wait for the command to finish running before you can run another command.

Background Process

Background processes run independently of a user and do not require interaction with the user.

You can run a background process by adding & to the end of a command in the shell.

# Run "my_program.sh" in the background

> ./my_program.sh &

When running a background process through a shell, you do not have to wait for the command to finish. You will regain access to the shell once the process is initialized.

Daemon Process

Daemons are a special type of background process that runs unattended and is not under user control. They are usually started when the system starts, and they run until the system stops. A daemon process typically performs systems services and is available to a task or a user. They are started by the root user or root shell and can only be stopped by the root user.

An example of a daemon process is the cron process. The cron process handles various system tasks at regular intervals.

Zombie Process

A zombie process is a dead process that is no longer executing but is still recognized in the process table (has a process id). It has no other system space allocated to it. Zombie processes have been killed or have exited and continue to exist in the process table until the parent process dies or the system is shut down and restarted.

Process Creation

Processes create other processes using the fork or spawn system call. The process that creates another process is known as the parent process. Every child process created is given a unique process id (PID).

Init Process

You might ask yourself if processes create other processes, how is the first process created?

When the operating system first boots up, the kernel first creates a sched process (for UNIX systems) and is given PID 0. The sched process then creates the init process and is given PID 1. The init process creates all system daemon processes, user login processes, and manages all other processes on the system. It is considered to be the mother of all processes.

For example, when you launch an application on your computer, the init process is the one that creates that application process and becomes the parent of that application process.

An interesting example is a workflow of opening up your terminal and running the ls command.

- The

initprocess creates the terminal process and becomes its parent. - The terminal process then creates the

lsprocess and becomes its parent.

Since the ls process was run in the terminal process, the terminal would be the process that creates and runs ls not init. The process hierarchy would look something like below.

Process ID (PID) | Parent Process ID (PPID) | Process Name

-----------------------------------------------------

0 | - | sched

1 | 0 | init

10501 | 1 | terminal

10502 | 10501 | ls

Fork

When a process calls fork, the parent process is duplicated and the resulting child process is identical in almost every way to the parent. The memory space of both the parent and child will contain the same content. However, if at a later step the parent or the child modifies one of its variables, the modification will be local to the respective process. For example, If the child modifies a variable, the parent will still see its old value. If the parent modifies a variable, the child will still see its old value.

The fork system call is often called to parallelize work of the parent process. After the child is created, both the parent and child will continue executing run concurrently.

Spawn

The spawn process is used to load a new program or command and execute it. It is loaded with new code and new memory space. The spawn behavior is preferred in Windows.

For UNIX, the spawn behavior is done by combining fork and then calling exec. The exec call allows UNIX systems to call new programs. If exec isn’t called after fork, then the fork‘ed copy of the original process continues to run as a copy.

Interprocess Communication (IPC)

Independent Process

Independent processes operate concurrently on an operating system, and they do not affect other processes nor are they affected by other processes.

For example, a parent and a child process that are running concurrently and not sharing memory between each other even if the underyling program is the same.

Cooperating Process

Processes might need to communicate with each other for the following reasons.

- Information Sharing - Several processes may need to access the same file.

- Computation speedup - A problem can be solved faster if it can be broken down into sub-tasks to be solved concurrently (especially when multiple processors are involved).

- Modularity - It may be easier to separate a complex task into separate subtasks than having many processes run the complex task.

- Convenience - A user can run several programs at the same time to perform some task.

There are two main types of communication that processes use to cooperate: Shared Memory systems or Message Passing systems.

We won’t go over the communication types as it is not extremely common for developers to use them. However, if you ever come across a situation where it could be helpful, it is essential to know that they exist. This article covers interprocess communication in detail if you are interested.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Process_(computing)

- https://www.cs.uic.edu/~jbell/CourseNotes/OperatingSystems/3_Processes.html

- https://www.tecmint.com/linux-process-management/

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/1653340/differences-between-fork-and-exec

- https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/inter-process-communication-ipc/